Software Toolkit for Generalists (pt 2)

Business Models

This has been surprisingly hard to publish because at one point I had written almost 15 pages worth of content which became tiresome to read. Trying to strike the balance between things that are current and matter vs. too much detail. I hope this is helpful.

The Old Revenue Model

Back in the old days when dinosaurs roamed the earth and Wall Street carried Blackberries, enterprise software was largely very uniform.

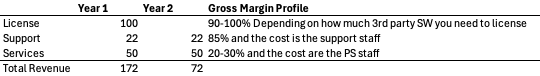

Company A charges company B a perpetual license to its software. What this means is the licensee paid a 1x fee to use the software forever (not the ownership the IP). The license is priced on some logical metric that aligned to scope (# of seats, # of devices, etc.) Then in order to receive updates, patches and bug fixes, Company A will change company B a support and maintenance fee usually equal to 20-22% of the value of license every year. In consumer software, think about the old Microsoft office disk - you bought it in a store and you owned it. In enterprise setting, what typically happened was the vendor established a very high list price for the software, then in sales cycles, licenses usually got discounted up to 80% to get to a street value. Then it made even more money by implementing the software - using either its own consultants (or 3rd party consultants known as system integrator like Accenture) to help customers configure, set up and get the system up and running. Often, the price of this service was can be 3x the amount of the license. So in numbers, the revenue model usually looked like this:

Cash flow more or less mirrored the revenue schedule since licenses were recognized up-front and paid. From a public market perspective, we focused on license revenue every quarter since that is the fundamental driver of the business. As you’d expect, there was a lot of lumpiness on license but supported by a generally stable stream of “insurance” for support fees.

Early Day of SaaS

Fast Forward to early 2000s, Marc Benioff came and said the traditional software model is broken, it created a mis-alignment of incentives between the vendor and the customer. The vendor’s objective is to maximize the value of the up-front license, and what happens afterwards was the customers problem. Instead software should be a service, where the economics of the deal was spread out over time so that if the vendor wasn’t continuously adding value, it would lose money when the customer cancelled early. AND, software is available on any browser and you got updates when you logged in!

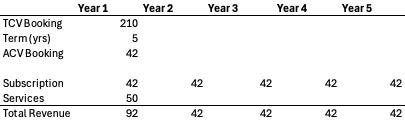

To spare you too much history, Salesforce, Workday and Netsuite, as early leaders in the new Software-as-a-service (SaaS) model, changed the economics of the industry and the model began to look a lot more like this:

The traditional software business model is predicated on the idea that you hired a group of engineers (fixed cost) to build a product and sell infinite numbers of times at minimal variable cost (commissions). The arrival of SaaS has changed the economics as every incremental deployment cost more data center compute and required continuous improvements to retain customers.

In the old license world, a customer bought a license and installed the software in its own datacenter. In the SaaS world, the vendor ran the software in the vendor datacenter so gross margins were lower. Early SaaS also tended to be much more out of the box and customizable so service requirements were generally lower. The biggest advantage was because there is a continuous dialogue between the customer and vendor, when the vendor came up with an another product, there was a very logical conversation to upsell.

From a public company perspective, you have a highly predictable recurring stream of revenue that in theory would accelerate if you continue to grow new business without losing existing business. However, the model is more more opaque in some ways:

Bookings (value of the contract signed in a qtr) is the forward indicator instead of license revenue. There are two types of bookings: New sale and expansion sale into an existing customer which could be selling more volume or another product (together, net new business) and renewals. Not only did companies not often disclose bookings, you wouldn’t be able to decipher new vs. renewals. Even if they provided bookings, it was unclear if you are comparing apples to apples year over year because some contracts can be 3 years and some longer or shorter.

Cash flow:

When you sold an up-front license, the fees are typically collected soon after signing. The value of the annual support fee is first put on the balance sheet as deferred revenue (its a liability of something you billed a customer for but haven’t delivered) then it burns off as revenue as you deliver the services with the passage of time.

In SaaS, there’s just a lot of variability. Say you sold a 3 year deal, sometimes a vendor will offer attractive discounts to customers to pay all 3 years up-front to help with cash flow, sometimes not. But the general rule of thumb is that the cash flow characteristics will look better than the income statement suggests. Invoiced but not performed portion of the contract becomes deferred, then recognized as services are performed (time).

Term License / Subscription License

If you want to be pedantic about it, SaaS by definition is a service where the application, hosting and support are grouped together into one element. So in that sense, it should be vendor hosted and sold as a “turnkey” solution to the customer to be SaaS. For new startups, that is usually the de facto founding model. But what about all the old companies that coudnt’t re-architect fast enough but also want a “SaaS multiple” or companies selling into regulated markets where customers have to host the application in their own datacenter for compliance reasons? Enter “Subscription licenses” which even today is very popular in private equity land.

What typically happened was you had effectively an on-premise application architecture, but instead of charging customers a 1x license, you mirrored the SaaS model by bundling license and support together and spread out the payment over multiple years and provided the customer the license right to use during that term. A customer can then decide to self-host or the vendor may take effectively an on-premise application and host it for them for a separate fee. The accounting for these licenses are much more complex. In some cases, certain duration of term are required to be recognized up-front as perpetual license and in some cases the support and license values are required to be carved-out separately. Suffice to say, financially this made many traditional software businesses look like SaaS without having to make the necessary R&D requirements.

Cloud Today and the Rise of Consumption Model

Fast forward to today, Cloud business model has advanced significantly but generally speaking, we have 4 flavors:

Traditional seat/metric licenses: There’s a set value for bookings and recognized ratably monthly over the contract term (e.g. Workday selling a HCM seat, or Gitlab charge by user per month). This is predictable to forecast.

Consumption model: This is the de-facto consumption model in most infrastructure software where the idea is the customer pays for what it consumes. For example, when you sign up for AWS online, you pay for their computers on a CPU/hour basis, you use x hours, you pay x hours. Same for for a virtual firewall where you are paying based on throughput. This is much harder to forecast because you are relying on the customer’s consumption forecast and how fast they can begin consuming depends on how fast you can get them up and running. More often than not, this is paired with a baseline predictable platform fee. Take Bill.com as an example, they will charge you a base fee to use their software + take a cut of payment volume.

Committed model: Similar to consumption except the customer is committing to an annual or multi-year spend. This allows the customer to obtain better pricing and the vendor to recognize bookings. For example, if customer A committed to spend $100M over 4 years, at the end of 4 years the actual usage will be trued up (or if the usage is less than $100M, customer still pays). The bigger the company gets, the more creative it can be with a commit model. For example, Microsoft would be able to go to a large customer and say - if you commit to spend $1B a year with us, you can use that pool of funds for any products. This type of customer control suddenly makes competition really difficult for best of breed point solutions. A customer may want Slack, but have a pool of money to spend with Microsoft, maybe Teams is good enough.

Developer centric / product led models: This is similar to consumer services where the selling motion is more akin to a freemium model that incentivizes immediate usage by a developer for free (with caps based on some metrics), then a per user per month fee to gain more features or caps, then an enterprise price that usually requires speaking to the sales team.

Go-to-market and selling model

The software go-to-market model is a complex topic. Without getting into all the nuances (Dave Kellogg has great articles about software GTM if interested), lets focus on the overview of the model:

In the on-premise / license sales days, a typical enterprise sales org had a head of sales who was in charge of selling license, a head of services who was in charge of selling and delivering services and a head of support. This model had many benefits but also 2 key draw backs in a customer centric world - (1) the responsibility for the customer experience sat with 3 people and (2) the sales guy was motivated to sell license and the service guy was motivated to maximize PS which often is at odds with what’s best for the customer.

Enter the Chief Revenue Officer role. Today’s SaaS sales organization largely places the customer in the middle with a CRO responsible for the majority of GTM functions. For the most part, PS is viewed as a enabler for product success and the sales org usually has one of two flavors: (1) Pure territory based, each rep gets a number of zip codes and is responsible for accounts in the territory (sometimes its by industry) or (2) sales is focused on selling to new customers and a customer success org is focused on “farming” or upselling new modules to existing customers.

Marketing plays wildly differently role within different types of businesses. The term you typically hear is corporate marketing vs. field marketing. Corporate marketing is branding, AR, etc and field marketing is tied to specific events and campaigns support the sales effort. Suffice to say that the closer a vendor is to the end customer the more reliance there is on field marketing activities to generate leads.

The typical forecasting model for a software business has 7 stages:

Lead => Qualified Leads => Lead nurturing (demos, meetings) => Proposal => Contracting => Closed/Won =>Renewal upcoming

so the new bookings model is actually quite simple:

Budgeted # of reps x full quota per rep = total booking capacity

Actual # of reps x actual quota attained per rep = actual bookings

A general rule of thumb is to think of raw pipeline to bookings as having a 3x coverage

Sales Efficiency

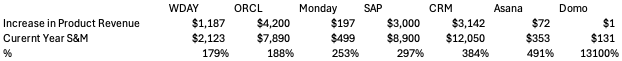

Efficiency is big topic in software investing because the relationship between customer revenue coming in and the cost to acquire the revenue is the single biggest driver of profitable growth. In early stage investing, the metric you are taught to focus on is the lifetime value of the customer relative to the cost to acquire that customer. I don’t find that to be particularly helpful in later stage or public investing. What I’m focused on is whether there’s natural growth in the market for your product? The biggest pitfall companies and investors fall into is this idea that growth is capacity constrained by the number of reps, so let’s go hire more reps and more revenue will show up! But that’s not always the case of course. In an ideal world (say you are a PE doing diligent with full information under NDA), you'd be able to see rep level attainment, measured against new and expansion ACV. In public markets you almost never have that level of detail, a back of the envelope math for me is looking at the yoy change in revenue relative to the total S&M cost expensed. You get a pretty interesting look at which companies have demand for its products and which ones do not.

The Analytical Framework

Some may disagree but to me the most important thing to remember is you are trying to make an investment, not purchase the technology. While having a strong technical background helps, particularly in early stage software investments, by the time a software company goes public, you are usually NOT taking technology risk. The risk you are taking is (1) Team has a firm grasp of what is happening in the market and can evolve with urgency (add new products, adjust sales velocity, make customers happy) and (2) Overpaying for a perceived trajectory that isn’t true (think Zoom growing another 30% yoy after COVID). keep in mind, as an minority investor, THE ONLY CONTROL YOU HAVE IS THE PRICE YOU PAY.

Levers

Ultimately you can make life a lot easier for yourself if you keep in mind that most software businesses are not that complex, the levers to pull are limited to:

You can ramp up and down quota carrying reps

You can change the quota structure and commissions to drive different behavior

You can focus on retaining existing customers and selling more to them vs. going after net new

You can increase or decrease R&D spend to bring forward of scrap roadmap products

You can be creative about how you license your product to customers

The end goal of cloud software businesses is a model where gross margin approaches 80% and operating margin approaches 35%, hopefully while growing topline continuously. In reality, this has rarely ever been the case. The natural tension is sacrificing margins to keep growing vs. profitability. The public market plays a large role in this pendulum in how we reward companies for growth (until we don’t).