Software Toolkit for Generalists

Part 1: Taxonomy and Fancy Words

What i’ve found is that in software investing, there often isn't a very useful place bridge the gap between the techie view of the world and the nuts and bolts modeling to translate into number. On one hand you have technical literature that really doesn’t serve any purpose when putting money to work, on the other you have sell side models that often miss the big picture. Then there’s Gartner and IDC which lays out things in such a markety way that it stops being useful. So here’s my attempt, hope it’s helpful.

Part 1 covers the basics primer from a practical perspective.

Part 2 will focus on the business model of software.

Part 3 the financial model mechanics and nuances.

None of these are absolutes but thought it would be interesting to share some of the taxonomy and modeling nuances we use to train generalists. I’m sure many of you can build more elegant models than me but the idea here is the principle of why you do certain things vs. the mechanics. I want to do this in a way that uses simple words to describe things vs. the jargons you see in most places that likely means nothing to most generalists.

First, let me assure you that enterprise software is extremely boring even though the ecosystem and buzz might seem splashy and sexy.

There’s this thing called a “cloud.” This basically means you have a giant warehouse called a datacenter. In this datacenter are rooms called data halls with racks and racks of computers (servers) connected to power. Some of these servers power general purpose workloads (CPUs) and some of these servers power very specialized workloads like AI (GPUs). Then these computers allow for applications to share computing resources and you can access them through the internet.

In enterprise software, there’s really 3 basic “stacks”

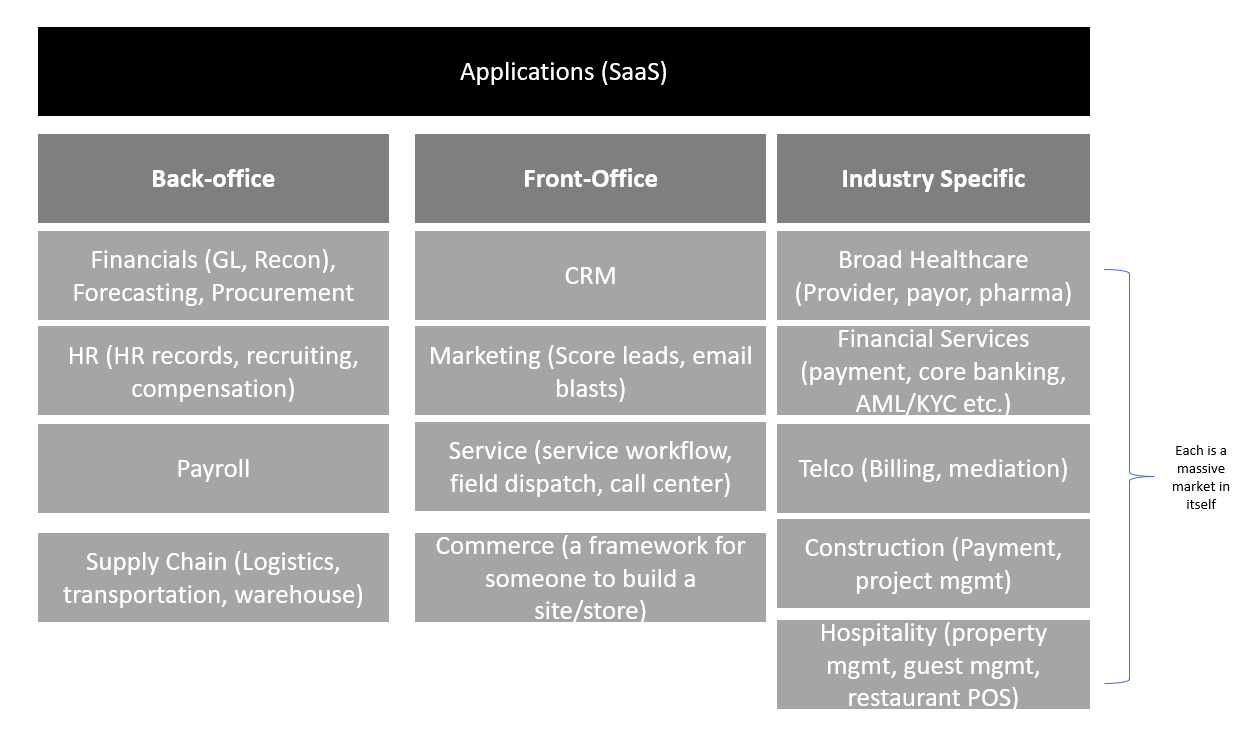

The applications that you use. People generally separate them into two categories: “horizontal” means financial ledger or a HR system that any industry can use. “Vertical” are systems specific to an industry such as software that lets a telco bill its customers, or a set of programs that allow banks to offer you online banking. Within horizontal, there are essentially two broad categories - back-office which are the HR, tax, finance, supply chain functions that are very important for large businesses and front-office - which are the customer facing software such as programs that let a sales rep type in a prospect (CRM) or a set of kits to let you build a website or storefront.

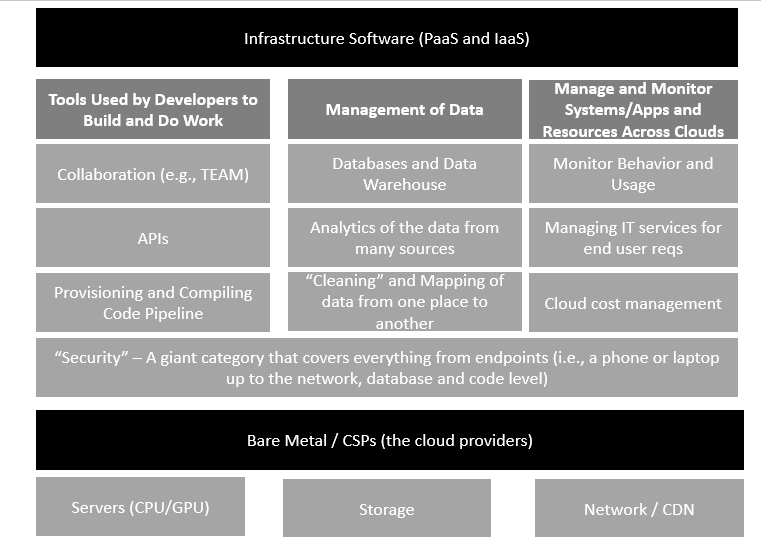

“Infrastructure” software is essentially the plumbing to allow systems to function well. There are alot more things in this part of the world such as an operating system or a software that helps different programs talk to each other and handle requests and deliver to the right place (called middleware and web servers), but for purposes of public market investors, there aren’t enough here these days to really call out separately.

Hardware or “Metal”. which is the actual physical machines that are sitting in a datacenter such as servers, storage boxes or network appliances. Oftentimes, these hardware devices are “virtualized” which just means it allows a machine to carve out resources so it looks like separate machines from a resource perspective.

So the next time you hear AWS - what is it exactly?

For the most part it is taking all these servers and storage boxes that it has sitting in a datacenter and renting it to customers by the hour and it makes a good margin doing it. Beyond that, AWS will offer you many many higher level services such as database, monitoring, and countless other things to you.

In the old days, a company would need to rent a datacenter space (from a colocation provider like Equinix), figure out your own datacenter design and rack your own servers. If you were starting a business today, the vast majority will choose to leverage a public cloud such as AWS, Azure, GCP or OCI which has done all the work for you. But it’s worth noting that despite the sheer size of these hyperscaler cloud providers today, the vast majority of large enterprise IT is still self managed. A bank is not ready yet to simply turn over their entire business to a 3rd party.

A small history tangent

The majority of the software companies that still exist today (and some are even thriving) from the last era tend to be companies who supplied plumbing to help large enterprises architect their datacenter. Companies like Teradata and Oracle remain the database backbone of the majority of Fortune 500 especially in regulated industries like banks, telcos, insurance, utilities. A key reason is volume of data + integrity of data + language dialects to translate schema. Contrast this with application companies of the last era (Peoplesoft, Siebel, Baan, JD Edwards, etc.) are either dead or consolidated.

Terms you hear often and what they mean

Workflow: Like the name implies, traditional applications basically map out a series of steps or actions based on the underlying work. For example, recruiting software will have a series of steps and sequences to follow from candidate identification down to onboarding. Workflows are usually out of the box with rules and configurations that every customer can make.

System of record (SoR): This is a single source of truth about a specific type of information. In any large organization, there are many many systems and subsystems where data is spread around. SoR are typically viewed as very difficult to put in place and equally difficult to replace as a result. Take an example of a CRM system, for anyone who has actually used salesforce, there are hundreds if not thousands of possible fields to set up in a variety of ways and once the system is set up for use, the users will type in data in a variety of ways which is often very difficult to aggregate so processes and procedures are then put in place to create rules for the sales team.

API (Application Program Interface): These are ways for applications to talk to another application. In the modern age, APIs are extremely important as every large company uses hundreds of applications and ability to communicate with each other is critical. It’s also worth noting that large companies realized that as they become the center of gravity, they are able to charge for tiers of API access “calls” through royalties. Salesforce, for example, has recently dialed up its API monetization in a big way in order to find growth.

Containers: Containers (such as docker) are ways to isolate code from the runtime environment so that you can “lift” it from one place to another. For example, you can containerize a cloud app and lift it into a on-prem or private cloud deployment quickly.

Marketplace: Every large cloud company has a marketplace. It offers smaller partners a distribution channel in exchange for revenue share. This may seem trivial, but for smaller software companies this can often be a meaningful revenue stream because it allows customers to purchase their goods with the cloud providers cloud credits (below). Some security vendors will drive multi-billion revenue streams from AWS alone.

Cloud credits: We’ll get into this in more detail in the business model section but think of this as exchanging a committed amount of cash for a cloud provider (AWS, Google, Azure) cloud credit. You can then use these credits to buy not only the cloud providers offerings but also its partner offers on the marketplace.

CI/CD: Continuous Integration/Continuous Delivery. Software development is a sweat shop factory. R&D organizations are constantly writing code, testing code, deploying them into a repository then into production environments like an assembly line. So naturally, software developers have come up with tools to automate and make this effort more collaborative, hence a series of vendors who now provide these developer facing tools to help with software development itself.

Stay tuned for part 2.

Great write up, looking forward to part 2 & 3